One of the side effects of my therapist role is that I'm continually in awe of the complexity of human consciousness.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the field of trauma therapy. Humans can face unimaginable pain and hardship, yet have an astounding resilience and capacity for adaptation. We are built for survival, and we find endlessly creative ways to adapt and morph our experience to navigate our way through challenging times.

We can convince ourselves that black is white, if that is what we need to believe to stay alive and feel protected. We can cut off and compartmentalise parts of our memory, experience, and reality to tolerate the intolerable. This is a large part of what can happen in psychotic states, and it is also part of how we survive trauma.

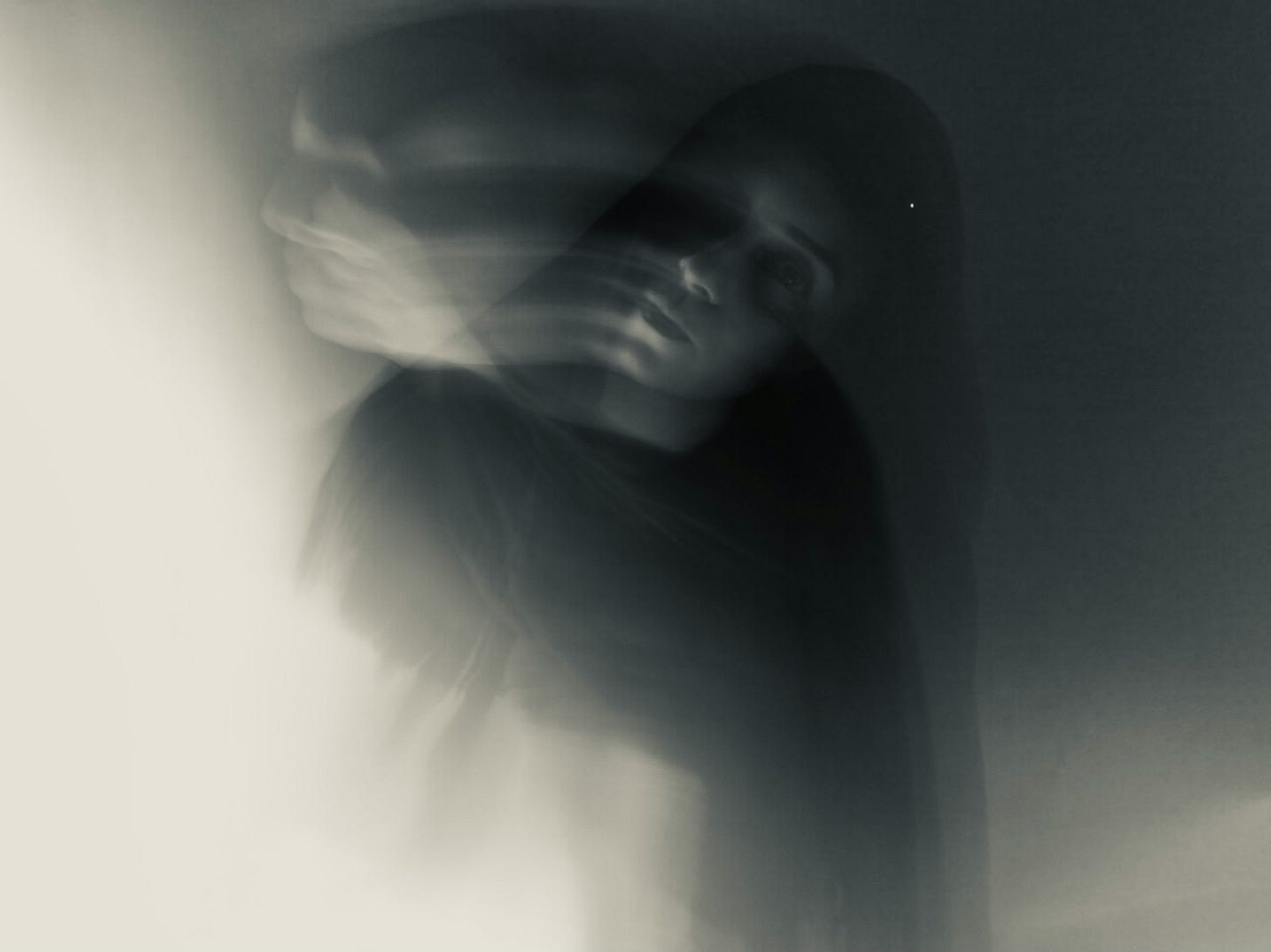

Dissociation exists on a spectrum. At the milder end are the everyday moments of checking out, where we are in conversation and realise we’ve completely missed what the other said – we were there in body but our mind was elsewhere. At the extreme ends, our experience of ourself exists in fragments. We switch between states without conscious awareness, and there are whole chunks of experience that are inaccessible to other parts of our psyche. We shut away parts of ourselves in metaphorical boxes in our mind. We stop experiencing ourselves as an integrated, cohesive whole.

At times in the mental health field, dissociation has felt like a shameful word, seeming to imply a failure to cope with life. But we sometimes forget what a brilliant coping mechanism this can be. We forget to thank our dissociative parts for helping us to survive when our options were limited, enabling us to bear the unbearable. Most people learned to dissociate at a very young age out of necessity to manage some experience in their emotional environment that was far too complex and overwhelming for their developmental stage. We were unable to leave, unable to exercise choice or power over our environment. We found a way to minimise the pain and intensity, while remaining physically present. No one had to instruct us how to do this. No one even could.

It reminds me of the tales of ancient yogis in India performing extraordinary feats of consciousness where their spirit temporarily left their bodies and existed simultaneously elsewhere, while in deeply meditative states. Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramhansa Yogananda is full of these tales. Whether these stories are mythical or literal is in the eye of the beholder, but I have certainly witnessed human consciousness perform some remarkable feats in the name of self-protection.

Dissociation deserves our reverence and respect. It deserves to be recognised for the life-saving coping mechanism that it is.

The difficulty and challenge of dissociation in daily life is that our human existence is very much experienced through the flesh, blood, and bone of our bodily form. When we dissociate frequently, we can feel as though we are drifting through life like a ghost, not quite connected to self, others, and our environment. We can feel like a shell of ourselves, distracted and unreachable, unable to connect to our joy and lifeforce energy. Unable to access deeper intimacy with others.

From a polyvagal theory perspective1, dissociation is driven by the dorsal vagal branch of our nervous system. A state where bodily functions like digestion, immunity, and reproduction are suppressed to prioritise our immediate survival2. It is hardwired into our biology. I have a cat who likes to hunt rodents, and I’ve witnessed many times the life-saving capacity that mice and rats have to freeze and ‘play dead’. It’s an involuntary response where they temporarily escape their sensory world to avoid pain, stay safe, and encourage a predator to lose interest. Humans have a version of this too when a stressful situation is inescapable. When both fight and flight are unavailable, we default to freeze. We check out.

It’s a short-term emergency mode that can become overused and habitual, particularly when we have been faced with ongoing overwhelming experiences from which we could not escape. Sustained time in this state can be associated with a range of health complaints and elevated inflammatory markers3. Our bodies are simply not designed to reside there long-term.

As we get older, if we have not cultivated a wider range of coping skills, these dissociative tendencies can draw us towards an array of substances, addictions, and distractions that help us to continue the pattern of escaping our reality, avoiding and numbing emotional pain. Our use of screens can sit on this spectrum – we exist in a disembodied virtual world, and to a greater or lesser degree, we shut off awareness of our emotional world and bodily experience.

When dissociation shows up in the therapy room, we offer it respect and curiosity. It communicates the person's limits and is momentarily enforcing a boundary that says - No, too much, not yet, unsafe.

The work is not to get rid of it, but to recognise it as an overzealous protector, and to know when it is not needed. To become aware that the adult version of us has a different kind of agency, choice, and power, and can protect our vulnerable parts in a range of other ways. To recognise that we can become fully present and find safety here. That we have capacity to be with and roll through the spectrum of human emotion.

The healing work is to be able to more fully inhabit the flesh and blood body while we're living this human existence. To more fully inhabit the vehicle through which we can know pleasure, joy, sensuality, grief, rage, and the full spectrum of human experience.

Dissociation gets to stay in the toolbox, but the toolbox expands to include a range of other options.

We work to find connection back to all parts of ourselves, without rushing this process. We slowly build our capacity to connect to what has been shut away. We work to gently expand the window of what we can tolerate and hold in awareness before needing to check out. We seek to expand the range of possibilities.

Instead of dissociating in a toxic relationship environment, we can find ways to enforce boundaries, voice our anger, or leave. Instead of dissociating from our emotions, we can learn to meet them in the body, build tolerance for uncomfortable sensations, and find ways to move through them. Instead of disconnecting from our environment, we can learn to return to our five senses and reclaim the joy, delight, and sensory pleasure of food, nature, movement, and sensuality.

This is the work of embodiment. This is the work of healing the ruptures within ourselves, tending our wounded parts, and reclaiming wholeness, vitality, and aliveness.

Dissociation is highly protective, but it can be a limited way of living and experiencing the world. It saves our life and steals our life at the same time.

Thank you for reading. I’d love to hear your responses to this piece. Do join me in the comments to share your thoughts.

If you value what you read here, you can support my work by liking and sharing this post, and by becoming a free or paid subscriber to The Therapy Room.

Disclaimer - Content is intended for educational and entertainment purposes only, and is not a substitute for individualised mental health treatment or advice.

Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr Stephen Porges, breaks down the detailed physiology of the nervous system. Learn more here.

Browning KN, Verheijden S, Boeckxstaens GE. (2017) The Vagus Nerve in Appetite Regulation, Mood, and Intestinal Inflammation. Gastroenterology. 152(4) :730-744.

Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex - linking immunity and metabolism. (2012) Nat Rev Endocrinol. 8(12) :743-54.

This makes so much sense, Vicki. I was nodding along the whole way, thinking: our bodies are so miraculous and so wise. If only we can remember to trust them, give them what they need, not numb out their signals... They know our limits and are deeply attuned to how those limits shift and change. You capture this so beautifully here. ❤

“Instead of dissociating from our emotions, we can learn to meet them in the body…” god I love that phrasing, meet them in the body. This was gorgeous.